Hello Fields Notes friends! Long time no write, sorry about that — I had a piece about the Mountain Valley Pipeline picked up by The Daily Yonder so I’ve been editing that and continuing to pitch other stories to other outlets and hunting down a full-time job, or at least two part time jobs? If I am ever fully employed and not just sending emails to Ira Glass begging him to let me do a story on social isolation in Eastern Kentucky, you will be the first to hear about it (Ira, please write me back). This is all to say this newsletter might be quiet for a while as I sort my life out, but as soon as anything of mine is published and out in the world, I’ll send a link and some backstory about the article with this Substack.

Speaking of, this Substack is in fact a democracy, and if you want a topic covered that I’ve missed or that you’re curious about, leave a comment! As long as it’s somewhat in my wheelhouse I’m happy to do a little extra research on it. In the meantime, this week I wanted to write about being local and what that means—and how it might differ from nativism.

I’m currently writing an article about Southwest Virginia’s growing solar market and one of my major questions is why some of SW VA’s red counties have had such success with solar projects (two SW VA counties agreed to put solar panels on all their school rooftops a couple years ago) whereas The Washington Post ran an article just last month about the intense disagreements over solar in a small Ohio town. A major point of contention in the Ohio case is the fear of massive outsider solar installers coming in from other states and building solar developments all over prime farmland, boxing some homeowners in amidst fields of panels. If you live in a small town where there hasn’t even been much small-scale solar yet, and the solar installer coming in from Vermont hasn’t shown a tangible interest in employing your grandkids, I can see how you would be skeptical.

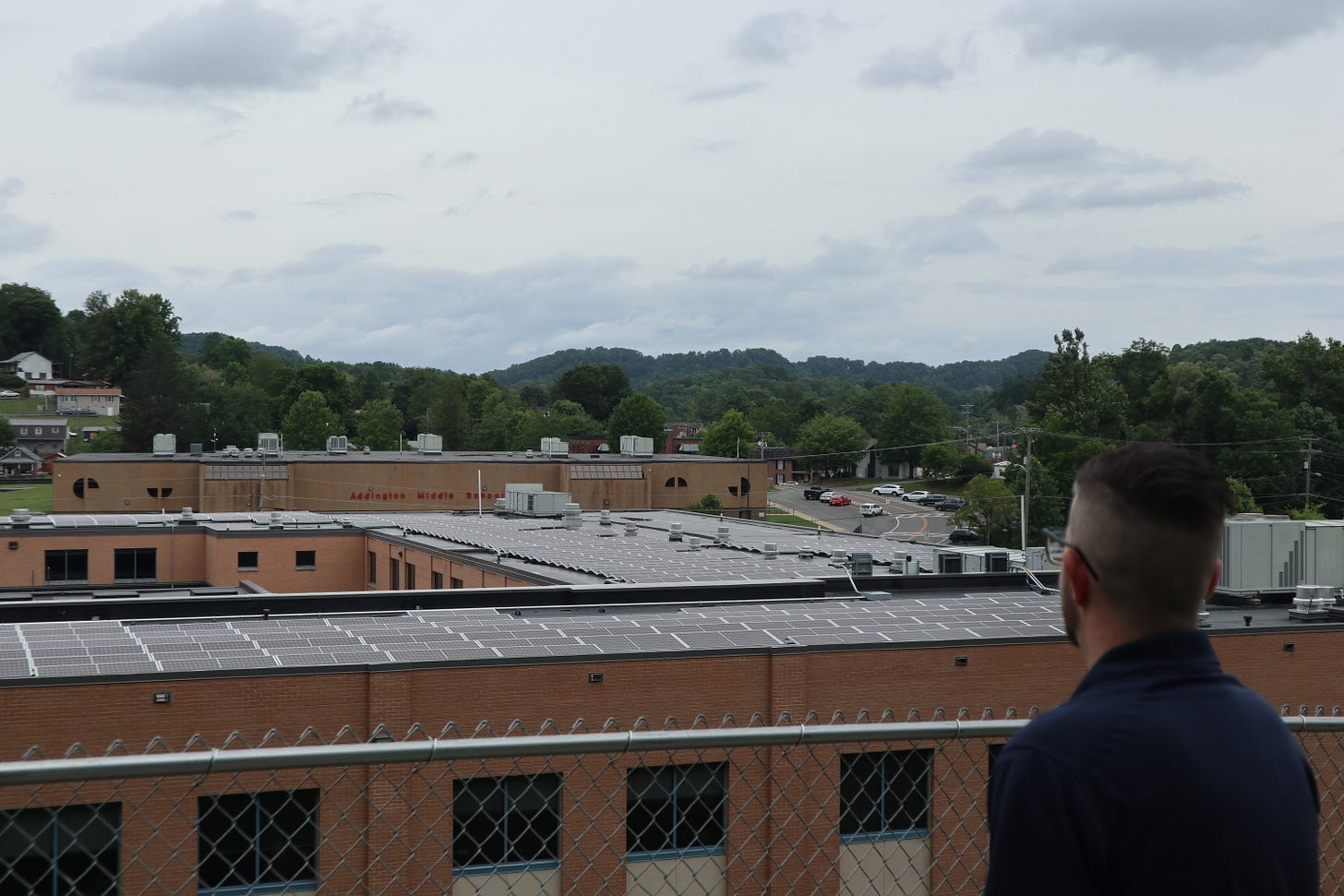

But in the case of SW VA’s Lee and Wise counties and their public schools, the solar installer they hired has a history of doing projects in the area—and the company’s business manager grew up going to the very schools he will soon be building panels on. He also runs an apprenticeship program where local high schoolers learn how to install and wire solar array systems for more money than Wendy’s will pay them. As he put it, “I try to do things right, because if I make mistakes in this process, it’s my name in the mud.” In other words, he lives nearby with his family and if he’d like to be able to keep living nearby, he better not screw anyone over—the estimated energy savings better be accurate, maintenance better be reliable, etc. Here’s a photo of him with one of his projects:

Being local, or showing serious interest in solving local problems, is especially important when there’s conflict over solar. One of my interviewees, who does outreach for a nonprofit that tries to make solar access easier in SW VA, explained that sometimes when people who didn’t grow up in coal towns see objections to solar, their first instinct is judgement, which isn’t productive. I’m putting her full quote here because it’s such a succinct way of explaining what “local knowledge” (a term used a lot by people studying environmental justice) means in practice:

“The minute somebody who is not familiar with the area sees resistance against solar, whether it's about concerns for the future, whether it's about concerns about displaced miners, or something else, the minute they see that, they're going to go, ‘What is wrong with these dumb hicks, why don't they know what's best for them? They've already lost coal. You know, they're stupid. They don't deserve anything. They don't deserve any effort.’ And I have seen that a little bit, people are like, ‘Well, what's wrong with them?’ And it's like, first of all, I'm from the coalfields. So watch yourself [laughs] And they have to understand. Coal mining: not just a job, right? The coal industry, not just an employer, right? It's not like Walmart. They built towns, they built schools, they built churches, they made their own money. You cannot really overestimate the amount of domination they had over these social and economic systems. And in my experience, the folks who tend to revert to that simplistic narrative are also folks who tend to be like, ‘Oh, those poor coal miners, their lives sucked so bad. They should be grateful it's gone’ with absolutely no understanding of the loyalty and dedication and pride that comes from that industry.”

But “local” can sometimes become a fickle term—something people call you when they’re happy with you and withhold when they’re not. A local mindset can become a nativist mindset, where the way we do things is simply the way we’ve always done them, no questions asked, and anyone who suggests a new way of thinking—regardless of local pedigree—is suspect. As one change-stirring interviewee in western North Carolina put it, “For people around here, you could have eleven generations of family here and it still isn’t local enough.” The work of changing nativist attitudes is slow and does require deep support from locals who decide that their beloved town does need a new energy source or a new water system or new members on the town council. That kind of years- or decades-long mindset-changing through conversation, demonstrations (I changed my gas stove and so can you! etc.), and building support is some of the toughest work out there, and the people who do it have my utmost respect.

Maybe Ira Glass isn’t my only hope, because I actually have an interview next week with a company based out of Huntington, West Virginia (home to Marshall University). Whether or not that ends up being my next step, it has me thinking about whether I could become local to somewhere else. It can be tempting, if you’re considering a move from a coastal city to a rural area, to think of it as a pitstop to somewhere else; flyover country. Somewhere you will surely want to leave when your time is through. That mindset is perhaps the only wrong way to be local: one-foot-out-the-door-itis. In our world of footlooseness (as I talked about before) I think it's typical for young people like me to think that we are never really home, only on our way to a final destination. But I don’t think that’s socially or psychologically healthy. My hope is that decades from now when I look back at the places I’ve lived, I won’t see stepping stones but instead a dozen little places where I have roots, making me one really big, beautiful, screwy-looking tree. Yeah. That sounds pretty good.

I like what you have to say in that last paragraph. I sometimes feel like the places I’ve lived are a bit too much of my personality like I moved from Louisiana when I was 7 but I talk about it a bunch and I sort of claim Chicago after only spending undergrad there, I also claim Mid Michigan to boot. I’ve often felt silly/self conscious about this but maybe I’m just good at avoiding the one foot in the door the other out itus. Thank you for changing my perspective