When I refer to the Mothman, the Flatwoods Monster, or Woodboogers in casual conversation, roughly half of people give me a blank stare and the other half immediately recognize the names (see images below). Central Appalachia, and West Virginia in particular, has a strong love for local beasties, monsters, and cryptids (folkloric creatures such as Bigfoot). Certain geographic areas are associated with certain creatures (usually the places where those creatures were first sighted): the Flatwoods Monster originated in Flatwoods, West Virginia, etc. Much to the excitement of older West Virginians who love to peddle tall tales, an interest in cryptozoology (the study of cryptids) seems to be resurging among young people. In Point Pleasant, you can now attend the annual Mothman Festival. Some articles I’ve read suggest that the town of Point Pleasant has experienced a salvific economic boom based on their Mothman-themed attractions (museum, gift shops, statue, Mothman-shaped pizzas). West Virginia’s tourism industry arguably runs on two things: the mountains and creepy crawlies. Any list of the top things to do in West Virginia is littered with haunted attractions: ghost tours, abandoned amusement park, abandoned psychiatric hospital, abandoned school, old burial grounds. Life is old there, older than the trees.

Maybe it’s just the people I happen to work with, but before moving here I’d never run into people so jazzed about the potential of abandoned buildings. West Virginia’s building stock is relatively old (most of the homes in my city were built in the 1950s) and due to population loss and economic depression post-coal, many homes sit abandoned or neglected, and the same goes for schools, factories, and stores that no longer serve bustling towns. People want something to do be done with these properties—if they are left unused or undemolished, they tend to catch on fire or collapse—but I also see an abandonment aesthetic that has emerged in West Virginia’s popular culture, perhaps a way of redefining the shame of dilapidated buildings and of learning to live with dilapidation in lieu of stronger programs for saving these structures. I’m not a sociologist or a folklorist, but I wonder if one of the ways to deal with decay without sinking into despair is to lean in to the creepy, the haunted, and the falling-apart.

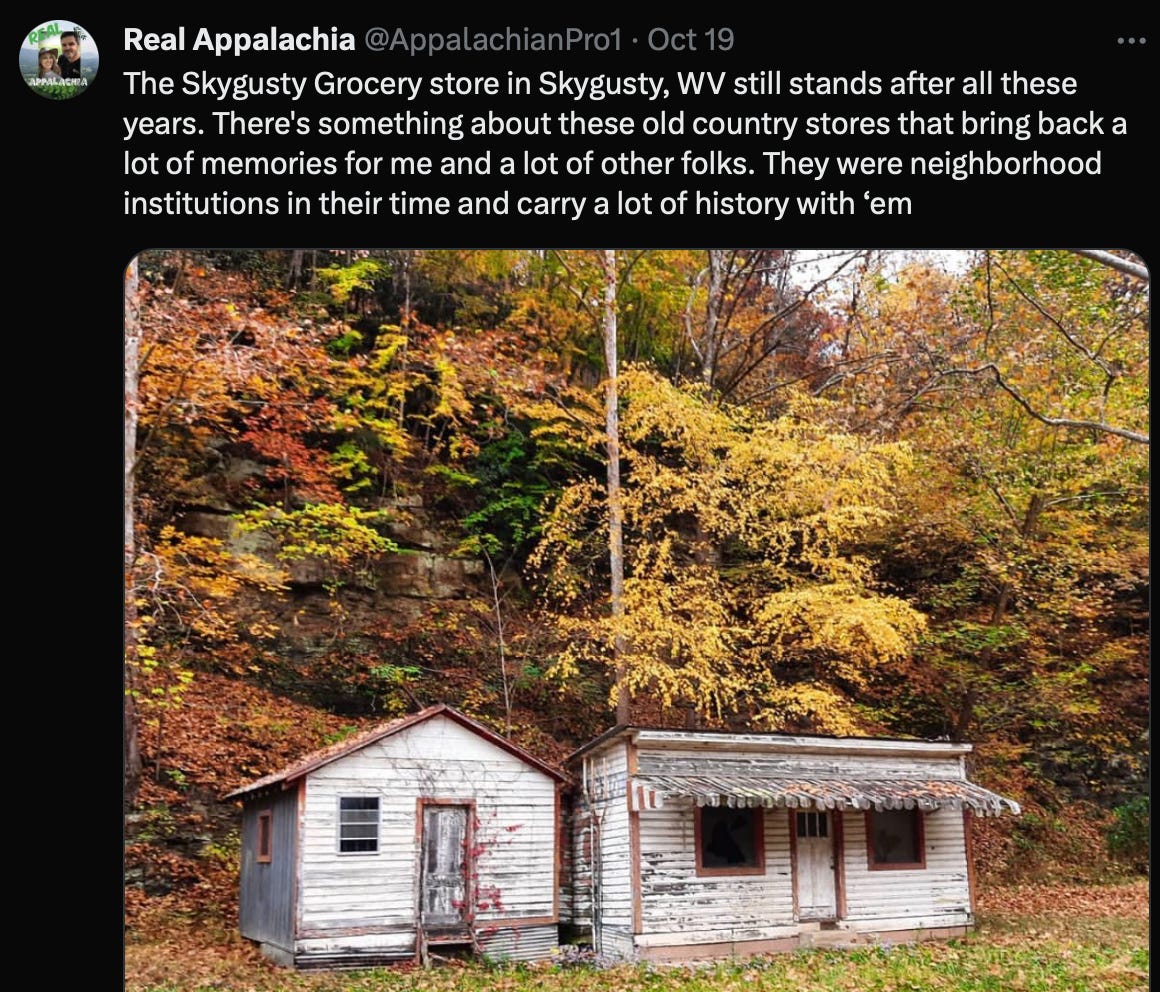

Take this post from Real Appalachia, the Twitter account for a couple who drive through small Appalachian towns and post videos on YouTube, sometimes as a means of discussing the state of tourism and historical sites in the state. From what I’ve seen, their content seems thoughtful and interesting, a treasure trove of nostalgia without any “I liked West Virginia back when it was whiter” sentiment, which, surprise! easily creeps into spaces devoted to historical photography/aesthetics. Anyway, sure, this building may evoke feelings of pity from people driving through Skygusty, but commenters below the post say the photo brings back fond memories of hometown country stores and one person writes, “I want to buy up every one I see.” One person’s creepy shack is another person’s longing nostalgia.

After all, the biological and physical process of decay that eventually cause roofs to cave in or old neon signs to flicker halfheartedly has no moral quality in and of itself. Rot can be aesthetically interesting or beautiful, it can be delightful to stumble on an old chimney or old shack in the woods and feel that you’ve struck gold as you wonder over all the people who lived lives with those structures. Decay is not malicious, it just is (in Elaine McMillion Sheldon’s film King Coal she says the same of coal: by itself, left alone, it is only a rock that has hurt no one).

Even eeriness can be delightful in a spine-tingling way. I mean, there’s a reason teenagers are known for hanging out in abandoned anythings – old factories, empty swimming pools, they love that stuff. Apparently we’ve had trouble keeping teens out of the old warehouse we’re restoring at my work (which becomes a problem when they mess with our equipment). This is all to say, the eyesore you might see on the side of the road could be a source of deep local nostalgia or a bastion of teen freedom – and it also may be objectively unsound and a fire hazard. This is why dealing with old buildings is a game of meeting in the middle. It can be extremely important to a community that abandoned buildings that *are* salvageable for some purpose or another retain their basic aesthetic or character. Staying and watching everything deteriorate is one kind of pain; staying and watching those deteriorated things get blown apart and replaced with sleek, all-glass modern boutiques that scream “This is not for locals or anyone remotely scruffy-looking!” is another degree of hurt altogether. There are a few different places in West Virginia where I’ve seen some good-faith efforts to remedy structural unsoundness and put a building back to use without making it look wildly different than the architecture around it. I’ve seen an old pharmacy turned into a museum, for instance, and an old bank with a shattered roof restored as some kind of greenhouse and art gallery (no roof, no problem! The greenhouse part seems to be in the process of getting a transparent glass or plastic ceiling).

This has me thinking about how I would renovate my own home one day, if I bought a fixer-upper. If the brick was dirty, would I take a power hose to it painstakingly or would I just paint it over with what one of my annoyed neighbors referred to on Twitter as “house flipper gray”? (Even if you don’t think you know what this color is, you do.) I didn’t think gray paint could be so divisive, but I’m beginning to see their point. “The character of the neighborhood” isn’t just a phrase that NIMBYs say—I think there is some legitimacy to being uneasy about people building hyper-modern homes in a neighborhood full of old brick bungalows built by railroad workers, or whatever the case may be. Deliberately avoiding scrapping the bones of a home signals that you might care about the community’s history or can recognize valuable materials instead of sending them to the landfill (Appalachians in particular appreciate smart repurposing and salvaging). As “house flipper gray” insinuates, painting over old brick may also be a way for folks looking to buy low and quickly sell high to paint over (literally) certain flaws. As one house renovator on a Reddit comment board I was perusing noted, “preserving charm is expensive.”

I’m getting the Appalachian salvaging bug (or maybe I always had it so it’s intensifying)—these days when I spot an abandoned house I think: first of all, I want to crawl inside that and poke around, and second, that door is still intact and someone should rip it off, sand it down, and repaint it. As I drive around West Virginia I feel a newfound pull towards every weird museum, neglected historical site, and haunted attraction. Someone’s gotta buy those tickets and support them! Someone’s gotta love all those ghosts!

P.S. I had an article published in Grist! This one has probably reached the greatest number of people so far and I’m proud: How to Sell Solar in Coal Country . I had a lovely time with their editorial team and a byline in Grist is definitely a badge of honor for an enviro reporter (they exclusively do high-quality enviro reporting) :)

Know someone who’d like my writing? Click this button!

We’ll, my dear girl, you’ve done it again! This article about ghosts is fun and thoughtful! And congratulations on being published in GRIST! You are blooming, Hannah, and I’m so happy to watch it!!🤗